Nearly two decades after Hurricane Katrina, the people of New Orleans continue to be a testament to hope, ingenuity and perseverance. Communities have done more than rebuild — they are reimagining systems to create opportunity for all, especially children. While significant progress has been made, critical work remains to ensure that growth is truly equitable and lasting. As part of an ongoing reflection series called Rooted In Us, W.K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF) staff and local leaders will share their perspectives on community efforts, lessons learned and the investments still needed to build a future where all New Orleanians can thrive. WKKF has been investing in New Orleans since the 1940s but named the city a priority place after Hurricane Katrina. As we look ahead, we remain committed to working alongside partners to strengthen economic opportunity,racial equity and community leadership for generations to come.

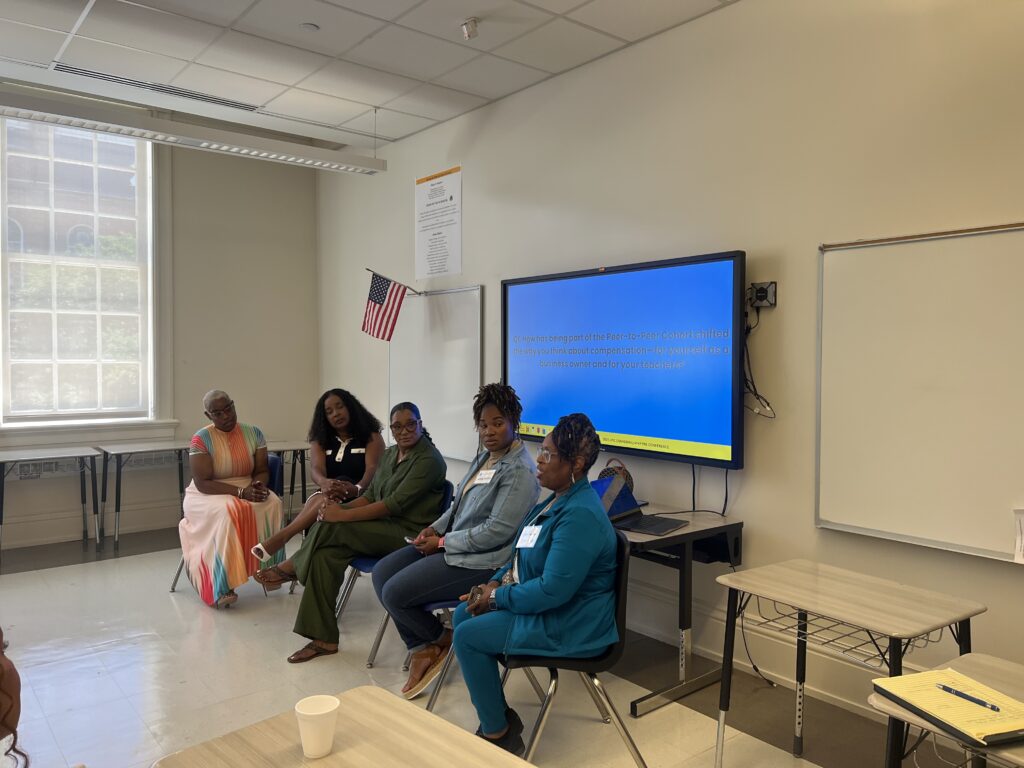

In this reflection, For Providers By Providers (4PxP) co-founders Rochelle Wilcox and Kristi Givens speak with Alyson Curro, a communications officer at the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, about the power of provider-led advocacy in shaping Louisiana’s early childhood education system. Born out of relationships forged in the years after Hurricane Katrina and formalized during COVID-19, 4PXP has grown into a statewide network ensuring providers have a seat — and a voice — at every decision-making table. Wilcox and Givens reflect on how they mobilized hundreds of providers, influenced policy in real time and continue working toward an equitable early care system that values, sustains and empowers the people who care for Louisiana’s youngest children.

Curro: I want to start with your reflections on those early days. If you’re comfortable: when Katrina hit, where were you and what do you recall?

Wilcox: I can’t believe it’s been 20 years. I think about how old my kids are now — I hadn’t even had one of them yet.

We were living in the Lower Ninth Ward. My husband and I were so proud. It was our first home. I’m an uptown girl, so I went to the Lower Ninth kicking and screaming, but it became our little space. We were young parents in our 20s with two boys, 6 and 8.

We lived near Sister St. and St. Claude, right by the levee breach. Our house faced the St. Claude bridge. At first, we planned to stay. I was working in hospitality then at the Delta Queen Steamboat Company. We’d been out on a work trip and got told to head home immediately. Katrina was being reported as a Category 3, but no one knew.

We’d just taken the kids to Gulf Shores, so I still had a bag packed. Then we saw a news story about a man who lost his wife trying to save their child. My husband said, “We have to go.” It was late at night. I grabbed important documents — birth certificates in a Ziploc — and we left.

We drove to Poplarville, Miss., and rode out the storm. Trees came down all around the house we were in, but none hit it. Meanwhile my mom chose not to evacuate. She ended up in the Superdome with my aunt and uncle. We lost all cell service. I put her on the Red Cross missing list. We eventually found her at Nicholls State. She stayed to care for older relatives while we went on to Houston, where we stayed for a year.

Coming back was complicated. My husband’s job sent him to Omaha, but that wasn’t going to work for us, so he returned to Houston. I came back to New Orleans and stayed with my aunt uptown until we could return. We lived in a trailer on my mom’s property — two adults, two kids and a dog — and it was tight.

While looking for a place to live, we saw a building I knew had been an early learning center — my niece had gone there. I could see it: “This is classroom one. Infant room here. Toddler room there. Look at this kitchen.” My husband said, “I know you see a vision, but we need housing.” A month later, he pulled up and said, “I took out my 401(k). Here’s the deposit and first month’s rent. I believe in you. Go do this.”

We opened Wilcox Academy on July 31, 2006, one of only a few centers operating within that first year. That’s our Katrina story.

Curro: As we come up on the 20th anniversary, what do your sons recall from that time — and how do they think about the anniversary?

Wilcox: My youngest was especially affected. In Poplarville, we were in a cabin with huge windows, getting the brunt of the weather. The men were bracing the walls. He clung to me: “Is the water going to come in? Are we going to drown?”

When we were finally allowed back to our house, we saw toys on top of ceiling fans, the water line high on the walls — 11 feet of water. He couldn’t understand why we couldn’t “go home.” He kept asking about the backyard playset — “the playground.” We had to show him it was gone. For years after, any heavy rain made him anxious: “Is it a hurricane? Will Dad have to hold up the walls?” It took a long time for him to feel safe again.

Curro: Kristi, do you want to share your recollections of those early days?

Givens: Before Katrina, we’d just opened our early learning center, and in June we bought our dream home in Slidell — four bedrooms, each of my three kids finally had their own room. Two were in college; I wanted them to be able to stay home into adulthood.

When the storm came, family members didn’t have money to leave. I put five hotel rooms on my credit card and got everyone out. We caravanned and eventually ended up in Georgia. At first, it felt like a weird vacation — cooking, laughing, thinking we’d be home soon. Then we saw the devastation on TV and realized: we aren’t going back soon.

I lost my business. Insurance didn’t cover what we needed; I didn’t have the right policy. Our house was fine, but the center was ruined. We’d also bought a building to open a laundromat — we were supposed to pick up the construction check Aug. 29. That didn’t happen.

We used our 401(k)s, sold a rental property, hustled to survive — I bought and resold items to keep paying bills. We rented out our house to a family to cover the mortgage. The stress was intense; at one point we literally had $1 left. I was depressed. Then Idea Village called out of the blue and offered $50,000 to keep us afloat — enough to cover insurance, utilities and hold onto the building while we figured out how to rebuild.

With help from other organizations, we eventually reopened Kids of Excellence. I also returned to social work for a while — counseling students in Plaquemines Parish about Katrina. Even years later, the trauma was so present. Little kids remembered the storm; high schoolers were angry. It was real.

Curro: Before Katrina, early childhood education in New Orleans was underfunded and uneven, with limited access for many low-income and families of color. After the storm, nearly all centers closed and the sector had to rebuild from the ground up. How do you see Katrina as a catalyst for reimagining — and in many ways building — the early childhood education (ECE) system we have today?

Wilcox: Katrina forced funders to collaborate and treat ECE as infrastructure — like hospitals, police, schools. Funders like the Kellogg Foundation invested and brought in others who hadn’t focused on ECE before. That attention helped people see there’s no economy without early care and education.

Givens: Exactly. Crises make people pay attention — Katrina, then COVID. But when the crisis fades, a lot of funding disappears. The Kellogg Foundation is an exception — they’ve stayed present.

Curro: What experiences as a provider led you to create For Providers By Providers? Was there a turning point when you realized providers themselves needed to be at the decision-making table?

Wilcox: After Katrina, there were more meetings and openings to plug in. The real turning point was the passage of ACT 3, where we saw huge changes but no providers at the table. It felt like things were happening to us.

When COVID hit, the informal relationships we’d built became lifelines. A handful of us started weekly calls — crying, venting, then problem-solving. Seven people became 25, then 200 across the state. We gathered data on who we represented and sent recommendations to the Louisiana Department of Education (LDOE). We saw policies change.

We realized we had to formalize it. That’s how For Providers By Providers (4PXP) was born: if you don’t have a seat at the table, you’re on the menu. Now we meet semi-monthly with LDOE and aim to have providers on every board that makes decisions.

Givens: And once we had numbers behind us, our recommendations started getting adopted overnight. It was empowering. That’s why 4PXP grew statewide — people saw change in their lives and believed in it.

Curro: Since Katrina, where have you seen the most meaningful progress in early childhood education? And what opportunities do you see right now to take that progress further?

Givens: Facilities are higher quality now, and salaries have improved. My staff went from $8 per hour back then to $19–$20 per hour now. I’ve watched families thrive because their children had safe, high-quality care. Parents became nurses, lawyers, entrepreneurs, teachers.

But the respect for early childhood still comes and goes. Babies don’t start at kindergarten; parents have to work. High-quality care is expensive, like college. If we invest early, we don’t need to build more jails. We’re missing data that fully shows ECE’s long-term impact.

Wilcox: I’ve seen more providers use their voices. But the pattern is painful. During a crisis, we get the sun on our faces; when the crisis passes, we’re forgotten. That’s why 4PXP keeps organizing — to sustain attention and investment beyond crisis moments. Our teachers deserve living wages and benefits; providers shouldn’t live in poverty for doing essential work.

We showed our collective power on the Day Without Child Care — 1,068 people on the Capitol steps. That kind of organizing gets noticed, and it changes policy.

Curro: This reflection will be seen beyond local communities — by national funders and policymakers who may not have lived experience with Katrina or time in New Orleans. As you sit with the 20th anniversary, what message do you want that audience to take away, specifically relating to ECE in Louisiana?

Wilcox: The biggest issue is consistency. Investment ebbs and flows. If it were steady, we’d be further along. Don’t give us lip service — invest. We’re in uncharted territory as a nation. Early childhood education, especially the first 1,000 days, is the infrastructure that will change outcomes. Invest in children and in the people who provide the care.

Givens: It feels like déjà vu. We hear there will be fewer seats next year as funding drops, while the nation says, “Go back to work,” and adds work requirements to benefits. Do the math: Someone earning $9 per hour can’t pay $1,200–$2,000 per month for child care. If we want people to work, we have to fund child care.

Katrina scattered families; the informal networks we relied on aren’t there the same way anymore. If we truly want better school outcomes and stronger communities, we must invest early. We’ve done everything we can to make the case — now it’s time to act.

Curro: Anything else you want to emphasize before we wrap up?

Wilcox: There’s no economy without early childhood education. None.

Want to learn more about For Providers By Providers and its work to ensure providers have a seat and a voice in shaping Louisiana’s early childhood education system? Visit forprovidersbyproviders.org to explore their advocacy, leadership development and statewide network — and see how you can support a future where providers are valued, families are centered and every child has access to high-quality early care and education.

Comments